Nov 07, 2017

Arrazolo Selene

First of all, let’s get this out of the way: Open data without an open data license is not open. The five points I’ll list here aim to help you as a data custodian make your data truly OPEN (saying it’s “open” is not enough). data.world is adding datasets from all over the world on a daily basis, as are our extraordinary community members. You’ll find the examples and literature cited to illustrate the challenges to opening data are primarily about United States’ city data portals, but these issues are not endemic to the U.S or cities. The Open Data Barometer’s recent Global Report found that “[only a quarter of the datasets analyzed] were available under an open data license — meaning licensing remains a big barrier for data use.”

To make data truly open, a license is necessary. Despite calls to license open data, there is little acknowledgment of what organizations are guilty of not providing a license. OKI grades cities and country portals annually in the Open Data Census based on the quantity and type of data they publish, but does not quantify licensing in their scoring. If datasets do not have clear licensing, then those portals could be publishing valuable data in vain. For example, even some cities at the top of the most highly ranked list in the OKI Census are failing to communicate their open data license, showing how even top portals are still missing the mark.

So, what are the 5 things that portals are doing to keep their data closed?

So… you think calling your data “open” makes your data open?

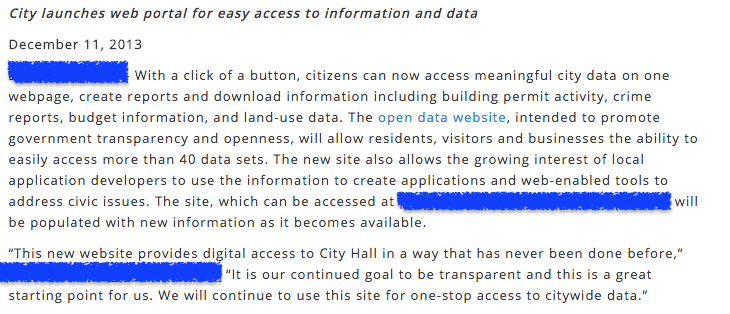

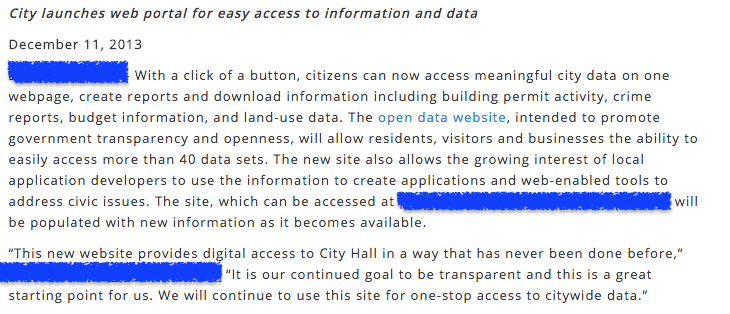

I call it not going the extra mile simply because some portals are so close! In the Sunlight Foundation’s Open Data Guidelines they clearly state that if data wants to be completely open it, “should be released completely into the worldwide public domain and clearly labeled as such.” There are several examples of organizations that declare their data is open, but do not provide a clear label that communicates their license. For instance, I came across this city’s press release from four years ago.

Though they list their expectations of how the data will be used, like “application developers to use the information to create applications and web-enable tools…,” it is now 2017 and their data still does not have an open license that would allow developers to do that lawfully. This example illustrates the misconception that making data available for download and stating your intentions to make the data open is enough, when without a license the goals the city outlined for their data are not possible.

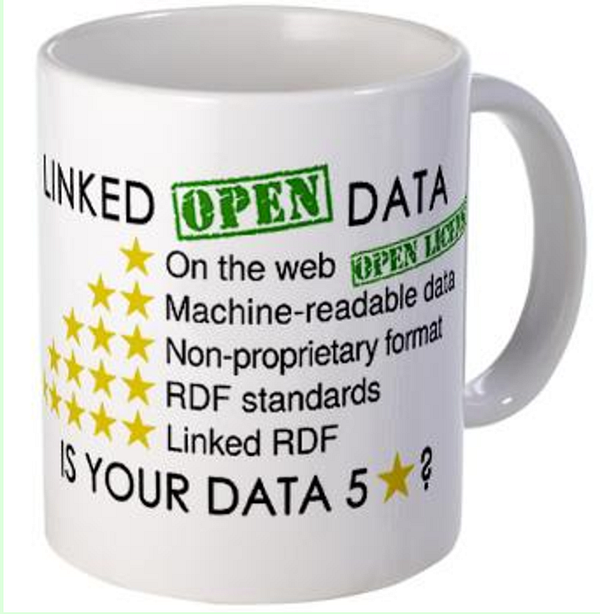

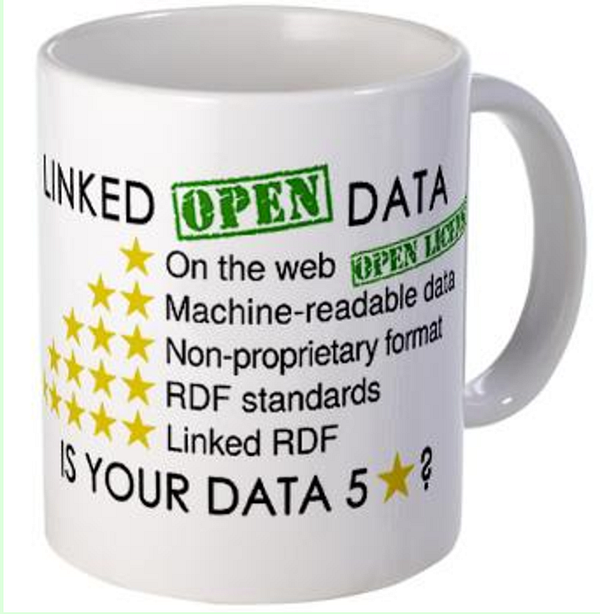

The Canonical Semantic Web Mug

The Canonical Semantic Web MugI want to take this opportunity to review the Five Star Open Data system. You might already be very familiar with it. It’s great for reference because it outlines the open data essentials: publish to the web, add open license, make machine readable, use non-proprietary formats, conform to RDF standards, and link data. “Open License” is in the first step because it‘s vital to open data (though even on the mug it appears as a rubber stamped afterthought). When making your data open, consider following the order of these steps.

PRACTICE TIP: Add a license. If you do not have an attorney on staff, consult the Creative Commons which provide great resources and solutions for people who want to make their data open. Go the extra mile.

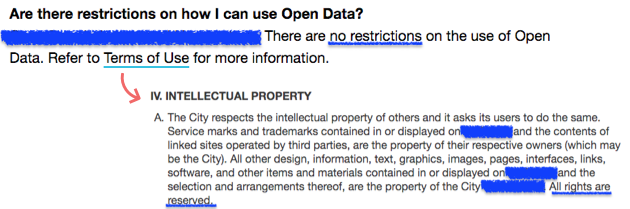

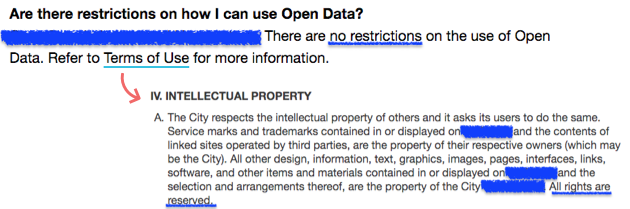

The data portal declares its data is free for all to download and share, but the terms of use (TOU) say otherwise.

Publishers are often not only leaving out a license, but they are also sending mixed messages. Boilerplate legal language is not necessarily written with open data in mind. It is likely that a site’s terms of use (TOU) were put in place independently, or before the open data portal existed. Though the intent is clear, a lack of license coupled with contrarian TOU cause uncertainty. In the example below, a large city explicitly communicates that the data can be used without restriction. Yet, they also point to their TOU which negate that entire statement.

Large city with confusing language

Large city with confusing languageIf they pointed to clear licensing rather than their TOU, there would not be an issue. In addition to conflicting internal legal language, consider the portal provider’s boilerplate language, which you might assume is supposed to serve as your license. Your portal provider’s TOU is very likely not written with licensing your data in mind, though the portal likely offers very well defined infrastructure to share your licensing information.

PRACTICE TIP: Get your legal language in sync. Take a second to review your TOU. Adding a caveat regarding the license applicable to the datasets on the site may be all that’s necessary to make your open data usable.

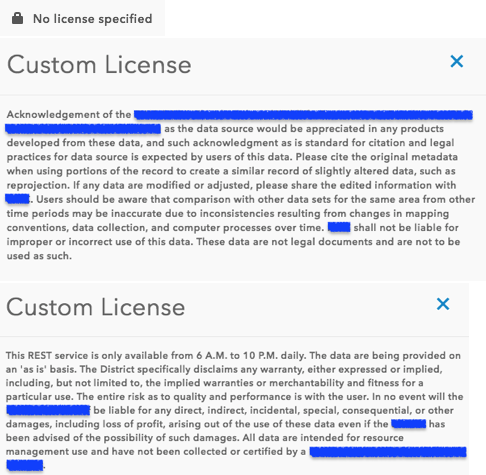

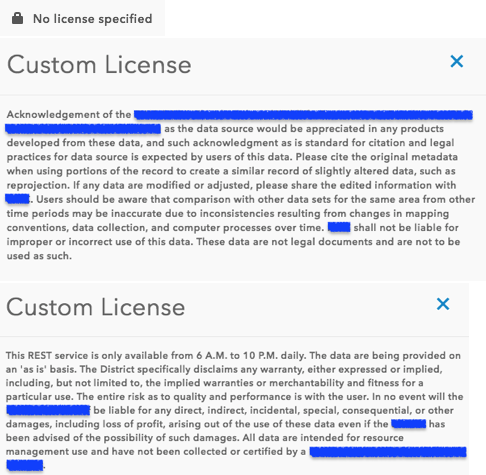

Available licenses don’t seem to fit your use case, so you shy away from choosing one, or you write inadvertently restrictive legal-like language.

When open data licenses you’ve found don’t seem to fit your needs, don’t skip on adding a license. Rather than leaving a dataset or your entire open data inventory license-less, consider providing a general license and adding exceptions to special datasets. There are cases where licenses are just not provided because specific instructions on how to use the data are seen as enough. In this example below I’ve listed three types of ‘licenses’ found in a single portal. The language is very specific, and very limiting as it does not provide a real license that you can personally attribute.

Besides choosing an established license, also consider licensing compatibility for derivative works or data projects. How will data consumers be using your data? Will adding special terms limit a dataset’s potential and re-usability? For instance, the CC-BY and ODC-ODBL both are open license which require attribution, but they are not compatible licenses. How do you want the data in your portal to be re-used and combined with other datasets to get to insights faster?

PRACTICE TIP: Choose a real license and communicate any specific changes/caveats to an already established license clearly. data.world’s article on Common License Types for Datasets is a great resource for understanding different licenses and how to use them.

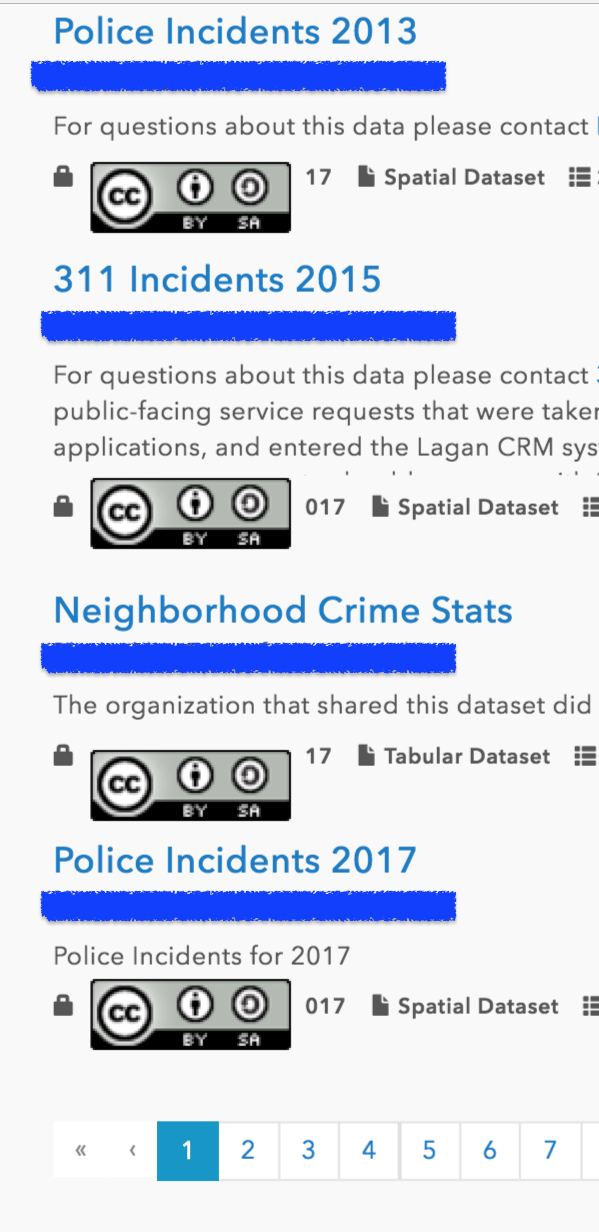

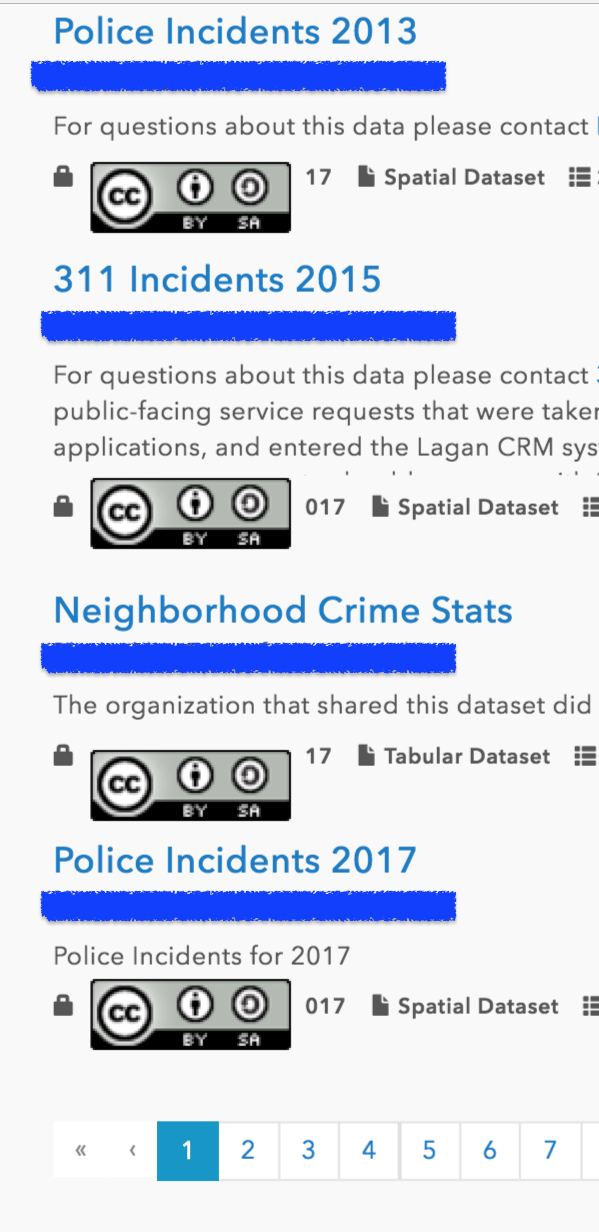

You’ve attributed an open data license, but you choose one of the non-commercial or share-alike versions.

Yes, a well-defined license is better than no license. Yet, a share-alike license (viral license) or one that restricts use of the data for commercial purposes (non-commercial) can force users to carry on a license for all future derivative works, in the former case, and prevent data consumers from ever making a truly commercial product in both cases. Here a city has published close to 100 perfectly useful datasets under a Creative Commons Share-Alike license, which means that anyone who uses this data or wants to develop a derivative work is required to always use the CC BY-SA license.

City data portal with a CC-BY SA licensed datasets

City data portal with a CC-BY SA licensed datasetsDoes this city really want to legally bind its data users? Anyone that creates new works based on the portal’s datasets is legally required to re-license those modifications under the same license, CC-BY SA, including all future derivative works created by others based on those modifications. This type of licensing can have a chilling effect on commerce if they are required to use a non-commercial license, reducing the potential for those datasets to solve larger societal issues. Before applying a license, take into consideration the following: who will be using your data, and what is your mission as an open data publisher?

PRACTICE TIP: Consider how you want your datasets to be used and re-used to help inform what type of license you choose. Choosing an open license and making it the default for all data on your portal removes the burden from the individual publishing the dataset to the portal, and allows others to use the data more easily.

The Creative Commons, and several online resources were made with folks like you in mind!

I’d be remiss to not go over the resources available for licensing. Ideally a legal expert on staff will help guide you, but the following resources are tailor-made for those looking to publish data.

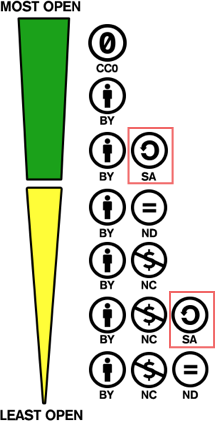

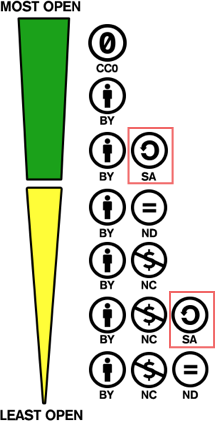

The licenses developed by the Creative Commons and Open Data Commons are recognized around the world, with Creative Commons taking the lead as the licenses of choice among dataset providers. As implied in the section above, there is a spectrum of licenses available for different use cases, but selecting a widely-accepted license will maximize the utility and potential of your datasets.

Creative Commons Spectrum

Creative Commons SpectrumRemember that the portals hosting your data have put a lot of thought into helping you share your metadata and communicate your license. Services like Socrata, CKAN, ArcGIS, and OpenDataSoft include a controlled vocabulary for your license, and provide a list of useful licenses to choose from.

We know there are often a lot of stakeholders in the data publishing process. These decisions can be intimidating and that’s why communicating your portal’s licensing policy internally from the get-go is crucial. Consider making license a required field for data publishers. This is a new rule some cities are starting to enforce.

PRACTICE TIP: Address what license applies to the datasets on the homepage of your data portal, and centralize all dataset licensing decisions under one group rather than leaving it up to each dataset creator or publisher.

Transparency, citizen engagement, and innovation are just a few of the many reasons why data should be open. In my quest to help share open data on data.world, I’ve reached out to several portal administrators, librarians, and CTOs. Many happy endings have come from simply reaching out, and I’d love to share a few.

West Hollywood, California — No License only Terms of Use (see 2.)

West Hollywood is a small city within Los Angeles with a relatively small data inventory. Yet it is West Hollywood, and they have wonderful datasets to share with the world like West Hollywood Filming Activity or Map of Open Art Installations. I reached out to them via email to see if there was a license they wanted to add to their data. Their attorney spoke with ours, and West Hollywood decided that the CC-0 License was what fit their needs and there are now 47 more datasets on the web with a license! Not only does their data in their portal now have a license but we have been able to share their data as well on data.world.

Las Vegas, Nevada — No License (see 1.)

The City of Las Vegas had done a wonderful job of publishing their data. They proudly shared their message of an open data philosophy on their portal’s page but had no license attributed to their datasets. After reaching out to Las Vegas’ Chief Data Officer, the decision to place all of their data under the Public Domain was a no-brainer for them, as it communicated exactly the level of openness they wanted for their data.

Durham, North Carolina — (see 5.)

Durham came to the Open Data Portal game prepared. They leveraged tools around them, reaching out to different organizations and asked for input before publishing their data. Now 100% of Durham’s data has an open data license and has been shareable, re-usable, and remixable since day 1.

Check out the City of Durham’s portal to see a stellar example of a portal that communicates their open data mission and open data licenses clearly, and has amenable Terms of Use.

Not sure what type of license to use for your data? Check out What License Should I Use For My Data? for a helpful guide and tools for picking the right license.

If you’d like to distribute your own data for others to use in a personal or professional context, read how you can use data.world for data distribution here.

First of all, let’s get this out of the way: Open data without an open data license is not open. The five points I’ll list here aim to help you as a data custodian make your data truly OPEN (saying it’s “open” is not enough). data.world is adding datasets from all over the world on a daily basis, as are our extraordinary community members. You’ll find the examples and literature cited to illustrate the challenges to opening data are primarily about United States’ city data portals, but these issues are not endemic to the U.S or cities. The Open Data Barometer’s recent Global Report found that “[only a quarter of the datasets analyzed] were available under an open data license — meaning licensing remains a big barrier for data use.”

To make data truly open, a license is necessary. Despite calls to license open data, there is little acknowledgment of what organizations are guilty of not providing a license. OKI grades cities and country portals annually in the Open Data Census based on the quantity and type of data they publish, but does not quantify licensing in their scoring. If datasets do not have clear licensing, then those portals could be publishing valuable data in vain. For example, even some cities at the top of the most highly ranked list in the OKI Census are failing to communicate their open data license, showing how even top portals are still missing the mark.

So, what are the 5 things that portals are doing to keep their data closed?

So… you think calling your data “open” makes your data open?

I call it not going the extra mile simply because some portals are so close! In the Sunlight Foundation’s Open Data Guidelines they clearly state that if data wants to be completely open it, “should be released completely into the worldwide public domain and clearly labeled as such.” There are several examples of organizations that declare their data is open, but do not provide a clear label that communicates their license. For instance, I came across this city’s press release from four years ago.

Though they list their expectations of how the data will be used, like “application developers to use the information to create applications and web-enable tools…,” it is now 2017 and their data still does not have an open license that would allow developers to do that lawfully. This example illustrates the misconception that making data available for download and stating your intentions to make the data open is enough, when without a license the goals the city outlined for their data are not possible.

The Canonical Semantic Web Mug

The Canonical Semantic Web MugI want to take this opportunity to review the Five Star Open Data system. You might already be very familiar with it. It’s great for reference because it outlines the open data essentials: publish to the web, add open license, make machine readable, use non-proprietary formats, conform to RDF standards, and link data. “Open License” is in the first step because it‘s vital to open data (though even on the mug it appears as a rubber stamped afterthought). When making your data open, consider following the order of these steps.

PRACTICE TIP: Add a license. If you do not have an attorney on staff, consult the Creative Commons which provide great resources and solutions for people who want to make their data open. Go the extra mile.

The data portal declares its data is free for all to download and share, but the terms of use (TOU) say otherwise.

Publishers are often not only leaving out a license, but they are also sending mixed messages. Boilerplate legal language is not necessarily written with open data in mind. It is likely that a site’s terms of use (TOU) were put in place independently, or before the open data portal existed. Though the intent is clear, a lack of license coupled with contrarian TOU cause uncertainty. In the example below, a large city explicitly communicates that the data can be used without restriction. Yet, they also point to their TOU which negate that entire statement.

Large city with confusing language

Large city with confusing languageIf they pointed to clear licensing rather than their TOU, there would not be an issue. In addition to conflicting internal legal language, consider the portal provider’s boilerplate language, which you might assume is supposed to serve as your license. Your portal provider’s TOU is very likely not written with licensing your data in mind, though the portal likely offers very well defined infrastructure to share your licensing information.

PRACTICE TIP: Get your legal language in sync. Take a second to review your TOU. Adding a caveat regarding the license applicable to the datasets on the site may be all that’s necessary to make your open data usable.

Available licenses don’t seem to fit your use case, so you shy away from choosing one, or you write inadvertently restrictive legal-like language.

When open data licenses you’ve found don’t seem to fit your needs, don’t skip on adding a license. Rather than leaving a dataset or your entire open data inventory license-less, consider providing a general license and adding exceptions to special datasets. There are cases where licenses are just not provided because specific instructions on how to use the data are seen as enough. In this example below I’ve listed three types of ‘licenses’ found in a single portal. The language is very specific, and very limiting as it does not provide a real license that you can personally attribute.

Besides choosing an established license, also consider licensing compatibility for derivative works or data projects. How will data consumers be using your data? Will adding special terms limit a dataset’s potential and re-usability? For instance, the CC-BY and ODC-ODBL both are open license which require attribution, but they are not compatible licenses. How do you want the data in your portal to be re-used and combined with other datasets to get to insights faster?

PRACTICE TIP: Choose a real license and communicate any specific changes/caveats to an already established license clearly. data.world’s article on Common License Types for Datasets is a great resource for understanding different licenses and how to use them.

You’ve attributed an open data license, but you choose one of the non-commercial or share-alike versions.

Yes, a well-defined license is better than no license. Yet, a share-alike license (viral license) or one that restricts use of the data for commercial purposes (non-commercial) can force users to carry on a license for all future derivative works, in the former case, and prevent data consumers from ever making a truly commercial product in both cases. Here a city has published close to 100 perfectly useful datasets under a Creative Commons Share-Alike license, which means that anyone who uses this data or wants to develop a derivative work is required to always use the CC BY-SA license.

City data portal with a CC-BY SA licensed datasets

City data portal with a CC-BY SA licensed datasetsDoes this city really want to legally bind its data users? Anyone that creates new works based on the portal’s datasets is legally required to re-license those modifications under the same license, CC-BY SA, including all future derivative works created by others based on those modifications. This type of licensing can have a chilling effect on commerce if they are required to use a non-commercial license, reducing the potential for those datasets to solve larger societal issues. Before applying a license, take into consideration the following: who will be using your data, and what is your mission as an open data publisher?

PRACTICE TIP: Consider how you want your datasets to be used and re-used to help inform what type of license you choose. Choosing an open license and making it the default for all data on your portal removes the burden from the individual publishing the dataset to the portal, and allows others to use the data more easily.

The Creative Commons, and several online resources were made with folks like you in mind!

I’d be remiss to not go over the resources available for licensing. Ideally a legal expert on staff will help guide you, but the following resources are tailor-made for those looking to publish data.

The licenses developed by the Creative Commons and Open Data Commons are recognized around the world, with Creative Commons taking the lead as the licenses of choice among dataset providers. As implied in the section above, there is a spectrum of licenses available for different use cases, but selecting a widely-accepted license will maximize the utility and potential of your datasets.

Creative Commons Spectrum

Creative Commons SpectrumRemember that the portals hosting your data have put a lot of thought into helping you share your metadata and communicate your license. Services like Socrata, CKAN, ArcGIS, and OpenDataSoft include a controlled vocabulary for your license, and provide a list of useful licenses to choose from.

We know there are often a lot of stakeholders in the data publishing process. These decisions can be intimidating and that’s why communicating your portal’s licensing policy internally from the get-go is crucial. Consider making license a required field for data publishers. This is a new rule some cities are starting to enforce.

PRACTICE TIP: Address what license applies to the datasets on the homepage of your data portal, and centralize all dataset licensing decisions under one group rather than leaving it up to each dataset creator or publisher.

Transparency, citizen engagement, and innovation are just a few of the many reasons why data should be open. In my quest to help share open data on data.world, I’ve reached out to several portal administrators, librarians, and CTOs. Many happy endings have come from simply reaching out, and I’d love to share a few.

West Hollywood, California — No License only Terms of Use (see 2.)

West Hollywood is a small city within Los Angeles with a relatively small data inventory. Yet it is West Hollywood, and they have wonderful datasets to share with the world like West Hollywood Filming Activity or Map of Open Art Installations. I reached out to them via email to see if there was a license they wanted to add to their data. Their attorney spoke with ours, and West Hollywood decided that the CC-0 License was what fit their needs and there are now 47 more datasets on the web with a license! Not only does their data in their portal now have a license but we have been able to share their data as well on data.world.

Las Vegas, Nevada — No License (see 1.)

The City of Las Vegas had done a wonderful job of publishing their data. They proudly shared their message of an open data philosophy on their portal’s page but had no license attributed to their datasets. After reaching out to Las Vegas’ Chief Data Officer, the decision to place all of their data under the Public Domain was a no-brainer for them, as it communicated exactly the level of openness they wanted for their data.

Durham, North Carolina — (see 5.)

Durham came to the Open Data Portal game prepared. They leveraged tools around them, reaching out to different organizations and asked for input before publishing their data. Now 100% of Durham’s data has an open data license and has been shareable, re-usable, and remixable since day 1.

Check out the City of Durham’s portal to see a stellar example of a portal that communicates their open data mission and open data licenses clearly, and has amenable Terms of Use.

Not sure what type of license to use for your data? Check out What License Should I Use For My Data? for a helpful guide and tools for picking the right license.

If you’d like to distribute your own data for others to use in a personal or professional context, read how you can use data.world for data distribution here.

Get the best practices, insights, upcoming events & learn about data.world products.